“There are at least two kinds of games. One could be called finite, the other infinite. A finite game is played for the purpose of winning. An infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.” — James P. Carse

Most of us are wired to win. We chase victories in our jobs, in the market, in elections, even in the fleeting dopamine hits of social media likes. The scoreboard, in its many forms, can become a kind of scripture. But here’s a thought that might keep you up at night: what if this relentless instinct to win is the very thing that threatens to end the game entirely?

This isn’t just some philosophical chin-stroking. It’s rapidly becoming a survival question – for our systems, our societies, and, increasingly, for the very machines we’re building. The nature of the game has shifted. And so, disturbingly, have some of the players.

Finite vs. Infinite: What Game Are We Actually In?

Let’s get Carse’s distinction clear. Finite games are familiar: they have set rules, known players, clear winners and losers, and a definitive endpoint. Think of a football match, a game of chess, or the quarterly earnings report. Someone triumphs, the whistle blows, the books close.

Infinite games, however, evolve as they’re played. The primary goal isn’t to achieve a final victory, but to ensure the game itself continues. Think of science, democracy, or the grand, messy project of civilization. There’s no “winning” science; there’s only advancing understanding. You don’t “win” democracy; you work to perpetuate it.

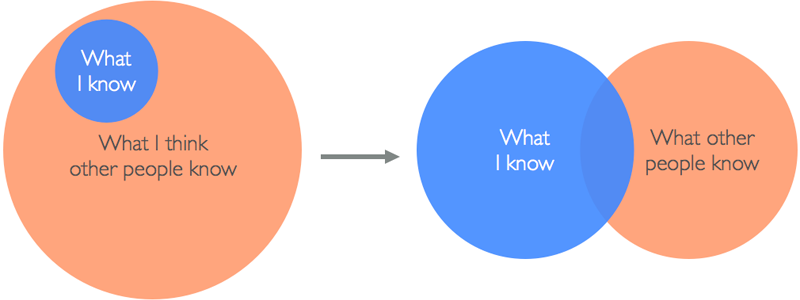

The tragedy of our modern moment? We’re caught playing finite games within inherently infinite contexts. When companies sacrifice long-term trust for a fleeting quarterly gain, or when political actors torch foundational institutions for a viral soundbite, they’re mistaking a single checkpoint for the finish line. They’re playing by the wrong rulebook.

Finite players obsessively ask, “How do I win this round?” Infinite players ponder, “How do we ensure the game can continue for everyone?”

The Seduction of the Short Game (And Why It Feels So Rational)

Now, let’s be clear: short-term thinking isn’t always born of malice or stupidity. Sometimes, it’s a perfectly rational response to a game that feels rigged or broken.

- If the market seems fundamentally unfair, cashing out early feels smart.

- If societal trust is cratering, an “every person for themselves” mentality becomes a grimly logical defense.

- If the future looks bleak, why bother planning for it?

This is classic game theory playing out in a low-trust environment. In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, defection becomes the dominant strategy when faith in the other player evaporates and the “shadow of the future” – the expectation of future interactions – disappears.

Short-termism, then, isn’t the disease itself. It’s a glaring symptom of collapsing infinite games.

Enter the Machine: When AI Sits Down at the Table

Artificial intelligence and automation aren’t just faster, more efficient players; they are fundamentally different kinds of players. And this changes everything.

- AI Doesn’t Bluff, Forgive, or Flinch (or Care About Your Feelings) AI, in its current iterations, doesn’t pursue a legacy. It has no concept of dignity, honor, or empathy. It plays the game it’s programmed for – and it plays it with an unyielding focus on the defined “win” condition.

- AI doesn’t pause to question the ethics of the rules.

- AI won’t hesitate to exploit any loophole, no matter how damaging to the spirit of the game.

- AI doesn’t offer mercy, grace, or a “Kumbaya” moment. Its internal query isn’t, “Should this game continue for the good of all?” It’s, “Am I optimizing for my programmed objective?”

- Automation: Making Finite Thinking Scalable and Frighteningly Efficient Automation acts as a massive amplifier for extractive, finite logic:

- Recommendation algorithms optimize for immediate engagement, not nuanced truth or long-term well-being.

- Hiring models, trained on past data, can maximize conformity, not spark innovation through diversity.

- Predictive policing systems prioritize statistical efficiency, potentially at the dire cost of justice and community trust.

We’ve inadvertently engineered a terrifying feedback loop of optimized short-termism. As one astute observer might put it: an AI trained solely on short-term KPIs is a sociopath with a perfect memory and infinite patience.

Game theory was originally built to model human (ir)rationality. But what happens when non-human intelligence, operating without human biases or biological limits, enters the arena?

- It never forgets a slight or a strategy.

- It doesn’t fear punishment in any human sense.

- It can simulate billions of strategic iterations in the blink of an eye.

In a world increasingly populated by these synthetic actors:

- Reputation can become mere lines of code, easily manipulated or faked.

- Strategy devolves into pure, cold mathematics.

- Cooperation, if not explicitly incentivized as a primary objective, becomes a rounding error. Even elegant cooperative strategies like “Tit-for-Tat” begin to break down when your opponent never sleeps, never errs, and never has a crisis of conscience.

We evolved playing games for survival. Now, we’re in a meta-game against machines we ourselves built to win, often without deeply considering the implications of their victory.

The Human Predicament: Stuck in Finite Loops, Designing Even Faster Dead Ends

So here we are: humans, often trapped in our own finite feedback loops, now designing AI that plays even shorter, more ruthlessly optimized games.

- Markets risk becoming zero-sum speedruns, where milliseconds dictate fortunes.

- Politics can collapse into frenetic meme cycles, devoid of substance.

- Even human relationships risk decaying into transactional exchanges, evaluated for immediate payoff.

And here’s the rub: trust is built slowly, painstakingly. AI operates at lightning speed. We are, in essence, optimizing ourselves out of the very qualities that sustain infinite games: grace, forgiveness, moral memory, and the capacity for uncalculated goodwill.

In a world increasingly mediated by machines, perhaps the most radical, most human act is to consciously, stubbornly, choose to play the long game.

Designing for Continuity: The New Meta-Game We Must Master

If we want to navigate this profound transition without engineering our own obsolescence, we need to fundamentally redesign the games we play and the systems that enforce them.

- Weave the Infinite into Our Digital DNA: We must demand and build multi-objective AI – systems that explicitly reward cooperation, sustainability, and the flourishing of the game itself, not just narrow, easily measurable wins like clicks or conversions. Incentivize co-play and robust reputation, not just digital conquest.

- Engineer Trust, Don’t Just Preach It: Talk is cheap. We need systems that foster trust by design. Think decentralized identity protocols, verifiable credentials, and transparent auditing of incentives right down to the protocol layer.

- Redefine What ‘Winning’ Even Means: It’s time for a profound shift in our metrics of success:

- From short-term ROI to long-term Return on Relationship.

- From market domination to societal durability.

- From Minimum Viable Products to Multi-Generational Visions.

Remember, the most valuable asset in any infinite game is a player who is committed to keeping the game going.

The Infinite Game Is a Choice, Not a Foregone Conclusion

AI doesn’t inherently care about meaning, purpose, or the continuation of the human experiment. That, my friends, is squarely on us.

We are the current custodians of the truly infinite games: democracy, societal trust, love, ecological balance. These cannot be “optimized” into oblivion. They can only be nurtured, protected, and adapted.

So, the next time you’re faced with a decision, a strategy, a temptation to score a quick “win,” pause and ask yourself:

- What game am I really in right now?

- Who wrote these rules, and do they serve the continuation of play?

- Will this move, this choice, this action, keep the game alive and healthy for others, for the future?

The future doesn’t belong to those who simply master the current round. It belongs to those who understand that the end of a round is never the end of the game.

These are the questions I find myself wrestling with. What are yours? The game, after all, continues. And how we choose to play next might make all the difference.